ABOUT ROBERT

Born in 1982, Robert Lemming is a Tulsa native who moved to Northwest Arkansas as a teenager. Having studied painting and printmaking at Henderson State University, and later finishing his BA degree at the University of Arkansas Fayetteville, Lemming’s work manipulates form and light to explore the nature of motion through the sculptural object. His ongoing series, Fucoid Arrangements, began in 2011 with sculptures that use trace fossils from the Northwest Arkansas region as a primary element. In dialogue with MIXD Gallery, Lemming extends context to the series, drawing from his early childhood memories, paternal figures, and geoscientific research to uncover the connection between his works and Drop 005.

MIXD: Can you tell us a little bit about your background growing up in Tulsa, OK and then moving to Northwest Arkansas as a teenager?

Robert Lemming: I grew up in a somewhat unremarkable way in Tulsa though my parents moved every two or three years but only two different places in Oklahoma and Arkansas. I did live in the country some prior to Northwest Arkansas, but mostly I had a suburban upbringing. My biological father died at 29 from a heart condition when I was 2 years old and I have only trace memories of the man, but my mom remarried rather quickly and the man she married, Gregory, who passed in 2015, was a very unconventional human being and couldn’t have been more perfect for a personality type like myself. He had lots of ear piercings and was a former professional drummer in the club scene. He had an interest in music and artistic things though very little formal training in either. I also left out because his father was one of the most unique characters I’ve ever met. He encouraged me greatly in the arts as a hypnotist and chiropractor as well as a World War II veteran. He made his own jewelry and furniture and collected strange artworks and sculptures from around the world. Going to his house was like going to a very idiosyncratic museum, and he let me go through almost all these collections of statues, toys from the depression era, odd paintings, and a huge pile of strange books with topics about paranormal research, ESP, hypnosis, and popular science. He had a collection of strange glass art with paper weights and giant ashtrays with organic forms and some of the paper weights even had small glass sculptures inside them resembling aquatic life and non-representational color swirls. I would look at these things and handle them for hours. It was a fertile ground for me, and he always kept me with art supplies and adopted me as his favorite grandchild. From a formative age, I feel like those two men really helped me feel comfortable in my natural tendencies towards abstract thought and unconventional attitudes and behaviors.

As far as art exposure, I really didn’t have much access to any art museums or anyone of my family that had much knowledge of art history, so I ended up naturally drawn to cinema, book and magazine illustrations, and comic books. Even then, I tended to lean towards things that were more abstract without really understanding that. I was very fortunate that I had those two people in my early development to encourage me and not judge me and a very blasé area of the country. When I came to NWA as a 13-year-old, it was in a rural setting just between Eureka Springs and Huntsville. We had to use antennas after a lifetime of cable. Video stores were far away, and the selections were often limited. I had been cut off from my small group of tight friends I had built in Tulsa in the last 4 years. That first summer alone I really had to more than ever find my own entertainment and inspiration. Though I always enjoyed parks and nature previously, I think it was this time where I really did learn to appreciate silence, deeper introspection and reading, and was able to dive even further into my own art for lack of anything to do. Because the area offered very little and my isolation from people my own age, I really did learn to be even more self-sufficient.

Throughout middle school and high school I did develop a very interesting and eclectic group of friends in the small Huntsville school. It was a major culture shock and there was left ethnic diversity that I was ever used to but I did find very interesting friends surprisingly in Madison county and as I began to visit their houses I started to see that the vast majority of the people I was hanging out with were the children of back to the landers, a term I wouldn’t learn for years later, people that came out during the 60s and ’70s to this part of Arkansas to live their own way in a homestead lifestyle with unique architecture opinions and often college educated parents. These interesting characters that I’ve begun to meet,and their parents really did give me a great sense of comfort in another wise very rural and restrictive agricultural environment. I took every art class I could in high school but really it wasn’t until I went to university at 21 that I got a more thorough and formal education in art history.

MIXD: When and how did first you begin making art?

RL: Really around 4 or 5 years old was when I started obsessively drawing. My parents realized that they needed to get me materials because I would draw on the blank pages in the front and back of all the books in our house if I didn’t have materials. My art was almost exclusively drawing and mostly black and white until college where I fell in love with almost every other medium and found its uses. Throughout my early years I was mostly drawing characters in landscapes out of my head sometimes from movies or comics but mostly of my own design. If I look back on those works now, I can see I was more interested in asymmetrical character design and abstract components and details, and I used the popular culture format to get to those things simply because it was the only format that I really knew. Toward my late teenage years, I started doing progressively more abstract and non-representational drawings and inkings.

MIXD: Can you elaborate on your series ‘Fucoid Arrangements’ and how tracing fossils from the NWA region became a central element of it? Can you walk us through your creative process?

RL: The fucoid arrangements series was a bit of a breakthrough for me in 2010 in my late 20s for a number of reasons. Many of the people I knew in my area of Madison County collected fossils that they refer to as bear paws and fucoids, but when I asked questions to elaborate on their nature no one actually knew anything about them other than that they were fossils. They like them for their aesthetic qualities, which I found equally fascinating. If you found one that hadn’t been too weathered, they had a series of high relief organic forms that overlapped themselves. If you were to guess what they were you would assume that they were a fossil of an ancient fern or plant of some kind. They could often look like wings of a bird or be more of an erratic overall pattern. I found myself collecting them in summers between university studies. At different points afterwards, I would work for a handful of land survey companies as a field man, and I would hike through very isolated parts of large tracts of property and come across things that haven’t been seen by humans in years from old cars to animal skeletons. These fossils would have occasionally been clearly visible in washed out gullies of the area.

My work often kept me over a mile from the truck over rough and treacherous terrain. The days could be approaching 100° with the humidity factor or below freezing, and I had to carry off a lot of heavy equipment in order to do my job. So if I found something deep in these undeveloped parts of properties like a fossil I had to be willing to carry it back with me throughout the day, and it took a lot of willpower and obsession to bring some of the choice pieces back with me.

Just as my collection of these objects was growing—and I consider myself something of a collector — I was at the University of Arkansas taking some painting and printmaking classes. I took a sculpture class and immediately found myself more drawn to three-dimensional forms and material. I began to think there might be a possibility for these to be incorporated into artworks, but I needed to know more about what they were. I reached out to the geoscience department at the University of Arkansas where I was studying studio art, and they let me know that they were not at all botanical. The fucoid name is actually a reference to an algae fossil that can be found of the same name, but these were fucoid structures. Things that were originally misidentified as something more botanical were actually trace fossils, like a footprint fossil, a memory of a movement.

When our region of Arkansas was an ocean bed hundreds of millions of years ago small arthropods would crawl along the ocean floor ingesting sediment in search of sustenance, these furrows and burrows were a byproduct as they would search for food. These would fill and become the trace fossils that I would find 300 million of years later. I was actually looking at a negative relief mold of the hollows created by these ancient sea creatures, bottom feeders.

Just the word refraction means a lot to my work, because I’m drawn to phenomena and artwork that can distort depending on perspective and data can be twisted and revealed through its nature. Light refraction refers to it twisting through one medium like air into water another medium. I personally switch mediums for sculpture and two-dimensional work at a whim depending on what the concept needs, and therefore refraction and a prismatic nature are actually incredibly late to my entire creative process.

ROBERT LEMMING

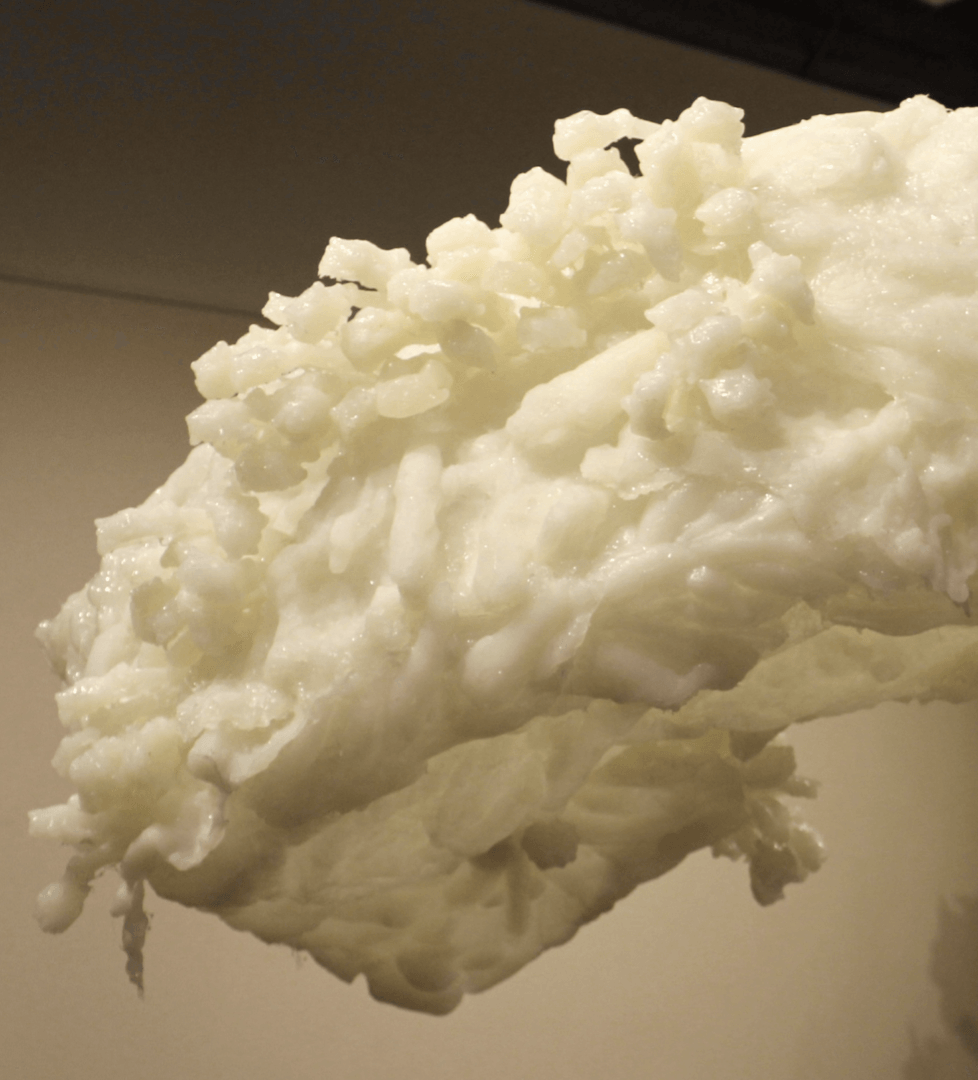

Armed with this knowledge, I started to create works using the fossils as a main component. Part of the reason was that I could be very controlling in my work’s design and by using elements that were already performed it forced me to make choices and adapt to the forms I had. That was actually a big step for me creatively, to let go of the wheel a little bit and innovate within my limitations. In that particular series those pieces would be made into molds and those molds would actually recreate the hollow areas that the creatures would make. I started using glue and silicone cast because of its flexibility, translucency, odd surface material, and ability to mold weld and manipulate it without much expensive equipment. By making them out of glue they became ghostly and all the movements of the creatures and then my movements refilling them with glue guns became visible simultaneously. These works led to the Burrows series in a natural way. The movement given physical space and material through the fossils and their reconstruction and manipulation made me want to create my own record of movement in a physical space that could be visible to the audience.

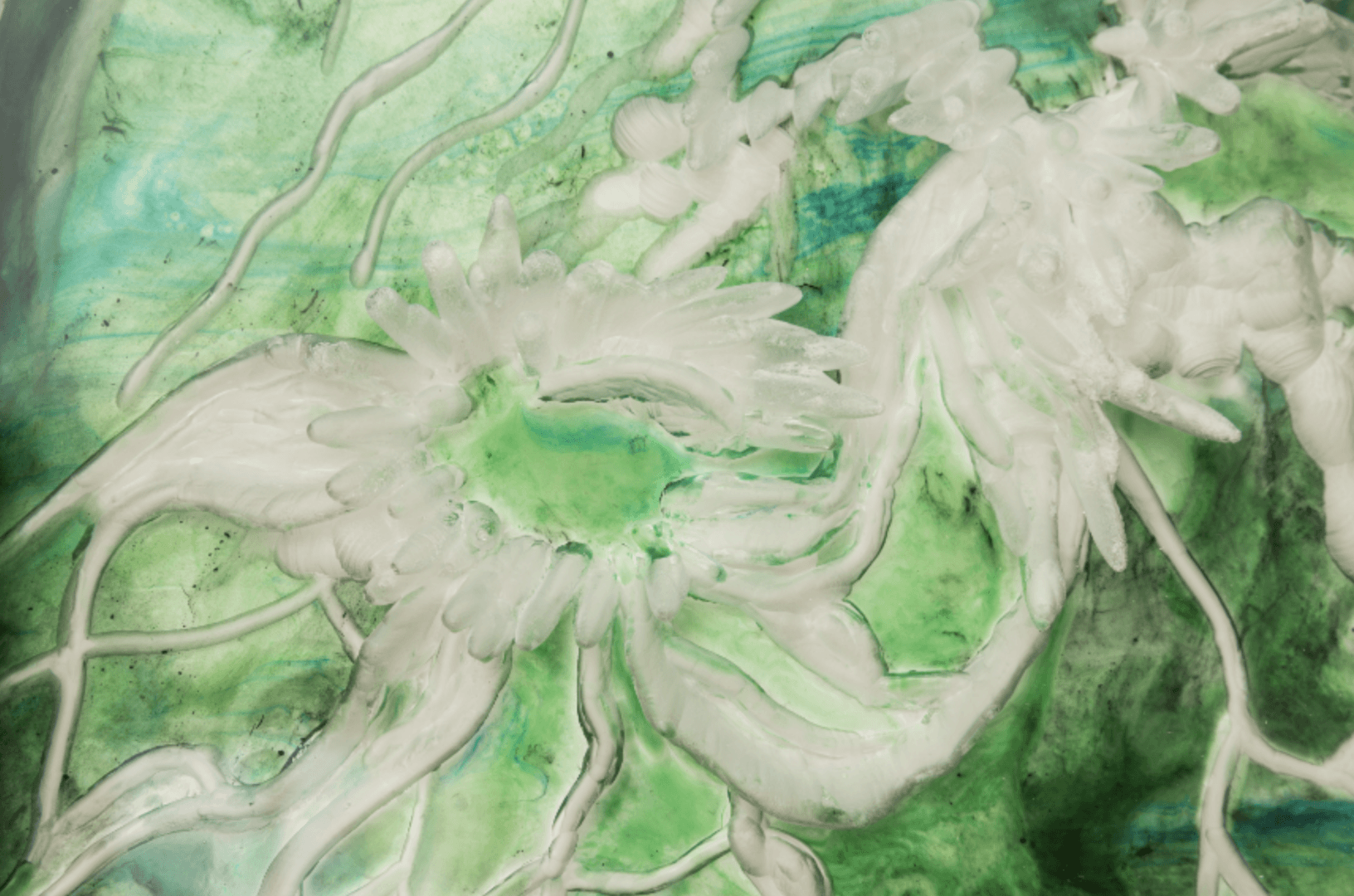

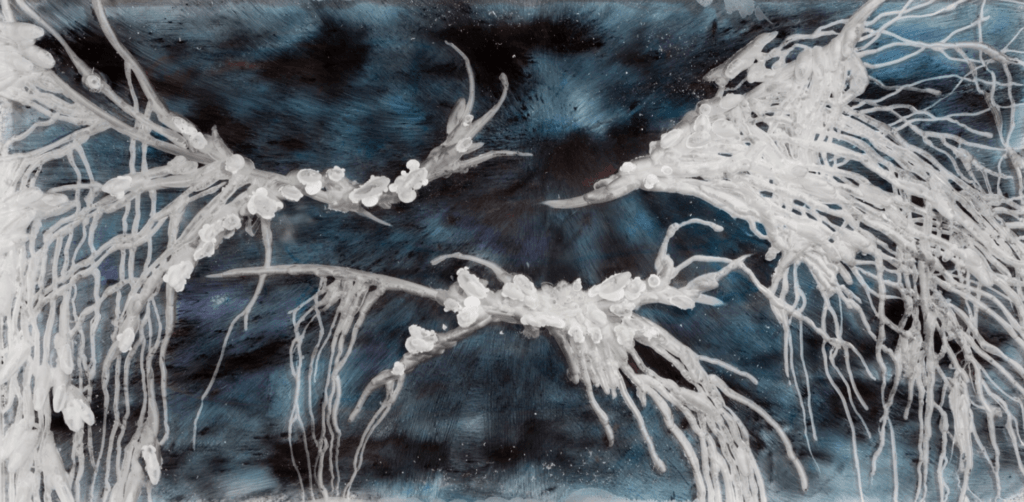

I started welding together multiple sheets of acrylic to get a very sizable thickness and then carving through the back side to make a visual surface that has a clean aquarium like outward facing component in a frame and the back side would be the parts that I carved into with heavy industrial tools like angle grinders and die grinders, drills and different heads for all of the above. Each one made its own type of mark and I couldn’t always control what they would do completely and I couldn’t see what they were doing in real time because I would be working on them back rather than the front of the surface. So I was working in a reductive fashion like relief carving but in a way where I was blind to its qualities. Again, creating works where I have less control and I have to react to the outcomes was more desirable. The overlapping movements and organic shapes created by these tools were my driving force in creating these works, and I draw a very clear line between the fucoid arrangement studies and works with the Burrow series.

MIXD: Have you considered exploring the metaphorical aspects of “Prism?” If yes, are there any symbols within your work?

RL: Metaphorically speaking, I think of the word prism and I think of Isaac Newton and his work and relationship to developing the color wheel, your understanding of refracted light and wavelengths. Something that is as scientific as it is magical is something that I can relate to a lot. Plus, the idea of translucency and light revealing components but also creating a deeper mystery is very appealing. Just the word refraction means a lot to my work, because I’m drawn to phenomena and artwork that can distort depending on perspective and data can be twisted and revealed through its nature. Light refraction refers to it twisting through one medium like air into water another medium. I personally switch mediums for sculpture and two-dimensional work at a whim depending on what the concept needs, and therefore refraction and a prismatic nature are actually incredibly late to my entire creative process. When I paint more frequently I like painting through cellophane and mirrors to paint something straight but distorted naturally. This has always been my first inclination when making work is to find a way to make the information go through a filter that requires effort on the part of the viewer.

A very warm thank you to Robert Lemming for entrusting MIXD Gallery to showcase his work and for joining us in conversation. If you’re interested in viewing more of Robert’s pieces you can find details here.